by Emily Previti and Stephanie Marudas | 2 December 2021

SHARSWOOD — With each thrust deeper and deeper into the earth, two young adults worked side by side digging holes in the ground. One gripped a pickaxe, while the other wielded a shovel. They hit rocks upon each strike. The work was strenuous.

As volunteers at Sanctuary Farm, their task was to make the holes deep enough to drop in wooden posts that would ultimately support a fence next to a new large metal-framed greenhouse under construction at the time.

With the greenhouse, Sanctuary Farm will be able to expand its growing operation from seasonal to year-round.

Standing nearby was Andrea Vettori. She provided guidance and encouragement to the two volunteers digging, while also supervising a third volunteer operating a rental skid steer machine.

Vettori started her career as a social worker and then became a nurse practitioner. She founded Sanctuary Farm to help grow and distribute produce, and still sees patients clinically once a week at a nearby city health center. But she spends the bulk of her time running Sanctuary Farm as its executive director.

“Healthcare is more than just treating someone’s diabetes or their hypertension. It’s a holistic approach to people’s lives,” Vettori said. “Being surrounded by green space, having healthy food, having a neighborhood that’s free of violence is all part of enhancing people’s lives.”

A purple banner hanging on the wooden fence provides information about a nearby farm stand where Sanctuary Farm distributes free produce.

When Vettori and a team of volunteers first broke ground in 2017, she said the main growing lot— which is located at North 24th and West Berks streets— looked completely different.

“It was filled with trash. It was filled with drug paraphernalia,” Vettori said. “The kids kept it somewhat clean because they were here playing in it. But trash was sort of on the perimeter.”

Today, this same corner lot is flanked by plants, flowers and shrubs abutting a brown post rail fence containing a lush garden.

Sanctuary Farm runs along both sides of North 24th Street, with the main growing lot and and the greenhouse across the street.

By the time summer rolls around, the raised beds are growing with various vegetables, including: lettuce, collards, kale, garlic, okra, potatoes and onions. Once harvested, Vettori and volunteers distribute the produce for free at a stand set up at Sanctuary Farm’s other site near Cecil B. Moore Avenue and North 22nd Street.

Sanctuary Farm has also become a regular neighborhood hangout spot where kids come to explore, garden, do art projects and play, Vettori explained.

“One of the kids in the neighborhood, every time he came out, he said, ‘I want you to build a tree house.’ And I knew we couldn’t build a tree house. But he said, ‘I’m going to go build a tree house.’ I said, ‘You go right ahead.’ And he would get whatever tools he thought he needed and picked up a few pieces of wood and just started playing,” Vettori said.

“But then he wanted a tire swing. I said, ‘Well, you find me a tire and I’ll put a swing up.’ So within 20 minutes, he was back with a tire.”

Priscilla Bennett, who’s lived in the area for 45 years, remembers when Vettori first came to the neighborhood and the advice she imparted:

“I said, ‘You’re going to have a problem. You got to get the kids involved in that if you want to sustain because you’re taking over their playhouse.’ “So she did and she created a children’s program with the kids and it worked.”

Project Home’s Helen Brown Community Center at St. Elizabeth’s, which is nearby Sanctuary Farm, operates a food pantry several times a week.

Bennett, who goes by Ms. Tee, works as the community engagement coordinator at Project HOME’s Helen Brown Community Center, just a block away from Sanctuary Farm.

Bennett teaches kindergarteners and first graders attending the organization’s Honickman Learning Center summer program and takes them to Sanctuary Farm to plant seeds and check out the beehives.

“You don’t see that very much…actually where your food comes from. And that was a good thing with the kids ‘cause a lot of them go to the corner stores to get their food,” Bennett said. “To actually understand and see a carrot pulled up out of the ground is quite fascinating, too. It’s like therapeutic for them as well.”

“It’s quite welcoming because she invites the neighbors to come and pick their vegetables, and whatever is growing at the time. They can be included in whatever is going on in the farm,” Bennett said. “That is something that is sustaining it…that inclusion is very important.”

Bennett said the operation has a “healing” effect as well.

“Green space is always therapeutic, especially when you’re living in a concrete jungle, and this is something nice and pleasant,” Bennett explained. “You don’t really realize the effect that it has on you, but it does, where you can just have a sigh of relief, like seeing something different.”

Recently, Vettori has wondered whether Sanctuary Farm’s existence in the neighborhood has improved community safety in any meaningful way. She is aware of research that shows greening vacant lots can have the positive spillover effect of reducing gun violence in the surrounding community.

One of the most widely cited studies around the country is one from 2018 that found a 29 percent decline in gun violence around stabilized vacant lots in Philadelphia.

But since Sanctuary Farm primarily focuses on growing and distributing produce— and relies mainly on health and wellness grants— Vettori does not operate any programming focused on gun violence reduction. She also has not collected any type of related data, though she says she’d “love to be able to measure” that kind of impact.

“I was thinking [of] going back to 2015, 2016, seeing what the gun violence rates were around this community. And then just looking now and seeing what they are,” Vettori said. “I’d be curious to see the numbers…, if there has been a difference.”

Is it possible to do the kind of analysis that Vettori’s proposing? Yes. But obtaining accurate data on local shootings is challenging. While it’s been well-documented that greening efforts make a difference, the process typically involves well-resourced researchers who can measure the efficacy of greening initiatives and therefore help contextualize these efforts within the space of public policy solutions that might be worth investing in.

Vacant Lot Management In Philadelphia

Several studies have probed vacant land management in Philadelphia over the years. But an especially prolific 2018 randomized controlled trial focused on the Philadelphia LandCare program, a well-established initiative between the city and the Pennsylvania Horticultural Society (PHS) to stabilize vacant lots.

Out of the city’s estimated 44,000 vacant parcels, PHS manages 12,000 and has stabilized 7,500.

Stabilization is the first of an intended many steps toward putting lots “back into productive use,” according to Julia Hinckley, policy director in the Philadelphia Mayor’s Office.

Basically, the stabilization process entails clearing, grading and hydroseeding, then adding a fence and, if the site’s large enough, trees, Philadelphia LandCare planning manager Samir Dalal explained.

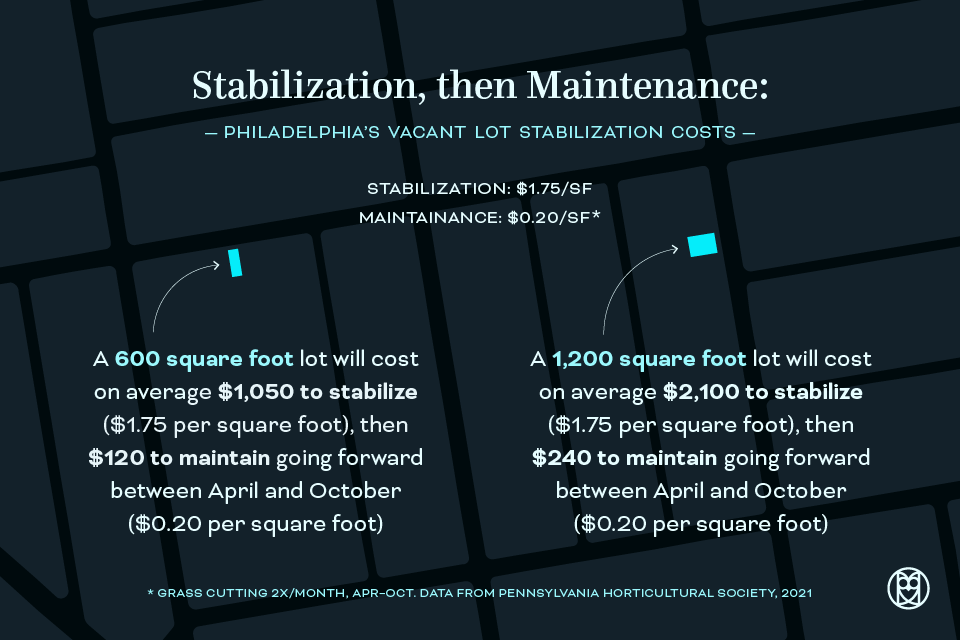

On average, it costs $1.75 per square foot for stabilization and the first year of maintenance, though “costs vary depending on conditions, location and amount of fencing needed,” Hinckley wrote in an email.

After a parcel’s first year of stabilization, Hinckley wrote that “PHS then spends on average $.20 cents per square foot to maintain a stabilized site for the growing season between April and October.” This type of maintenance consists of two grass cuts per month.

PHS spends around $3.4 million annually to manage about a third of the city’s vacant land, consisting of both stabilized parcels and lots that are not stabilized but still maintained, and works with outside contractors and community organizations to help do the work.

Hinckley wrote in an email that the city provides PHS with $2.89 million from its general fund, $377,000 from the Community Development Block Grant (CBDG) program and $1 Million for Same Day Pay. She noted that “PHS also receives funding from individual donors, foundations, and corporations to deliver workforce development training to train and place people with jobs, often with contractors and community groups that clean and green lots.”

The Big Picture

The takeaway from the 2018 randomized controlled trial is that scaling up cleaning and greening efforts could meaningfully reduce gun violence in Philadelphia: researchers projected 350 fewer shootings per year, based on the 29 percent drop in gun violence they linked to Philadelphia LandCare.

The study received enough media attention at the time of its release that it piqued the interest of officials in jurisdictions outside Philadelphia, including: Chester (Pa.), Cleveland, Dallas, Detroit, Newark, Youngstown, New Orleans, Chicago and several cities in Japan.

A glimpse/view inside the shed where various garden tools and supplies are stored at Sanctuary Farm.

In Chicago, the research prompted officials to spend more on vacant lot transformation as part of an effort to create jobs for individuals who were previously incarcerated, according to Michelle Kondo, one of the researchers who worked on the study.

Kondo, a research social scientist with the USDA Forest Service in Philadelphia, said that the RCT study has also led to increased funding around this type of work in general.

“We’re starting to see more funders that are willing to invest in this type of paired funding for both the intervention, the program side and the paired evaluation that would go with it, with a focus on violence prevention,” Kondo said. “It was sort of unheard of even five, ten years ago, before this study of the RCT was published.”

To that point, Kondo has since been working with cities such as Baltimore, Camden, Flint, New Orleans and Youngstown.

Kondo also collaborated on a related study published in 2016 examining the Philadelphia LandCare program through a cost-benefit analysis.

The researchers touted their study as the first of its kind “to report cost-benefit and percentage reduction estimates for urban blight remediation programs and firearm violence.”

Coordinating with PHS, they tracked more than 4,400 remediated vacant lots for nearly four years.

After a year, the researchers discovered remediating each lot yielded a $26 return on investment to taxpayers, plus $333 in societal returns on investment for firearm assaults. Over 46 months, they also reported there was a $77 return for taxpayers and a $968 return on investment “per vacant lot, from a societal perspective, for firearm assaults.”

“But there’s more. I mean, we’re finding people felt less depressed, who lived near the cleaned green lots,” Kondo said. “There are more and other different health related outcomes or impacts that we’re seeing that would have not been calculated in terms of return on investment, the benefits that we’re seeing.”

Kondo is still working with the data set that helped inform the 2016 and 2018 published studies. Specifically, she’s parsing surveys of people living near vacant lots that were part of the studies to determine “whether men versus women were equally affected in terms of their perception of safety or fear of crime,” Kondo said.

As for broader applications, Kondo pointed to a need for more research into the effects of specific design elements of remediated vacant lots. She said installing benches, for example, might encourage people to spend more time outside and interact with their neighbors.

Kondo also questioned how we, as a society, should think about vacant lot remediation.

“Can or should these intervention costs be considered public health or healthcare expenses or crime prevention? And so, should we be thinking about funding streams and sources?” Kondo asked.

Cleaning and Greening as a Violence Reduction Strategy

The various studies did help show that the Philadelphia LandCare program was effective, and spurred a new joint initiative starting in the fall of 2019 with the Philadelphia Police Department through its Operation Pinpoint initiative.

Operation Pinpoint is a citywide anti-violence effort that uses data to identify gun violence hotspots and implements various customized interventions that can help “reduce blight and improve environmental factors in high risk neighborhoods,” according to city financial documents.

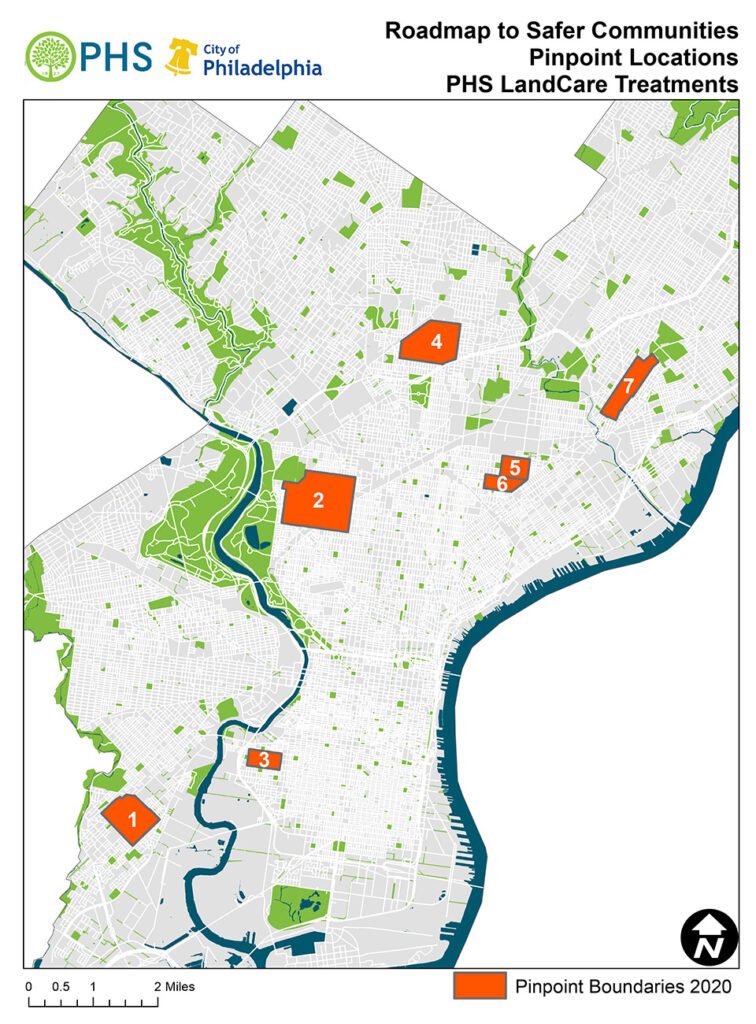

Through this initiative, PHS received $1.5 million from the city to work closely with the police department on vacant lot stabilization and maintenance in seven areas across the city experiencing high rates of gun violence. Between fall 2019 and summer 2020, PHS flagged more than 2,800 vacant parcels within those areas. Nearly 1,500 of them already were under some form of land maintenance. PHS went on to stabilize 270 new parcels and added a total of 970 lots to its overall inventory.

As part of this effort, 86 percent of the vacant lots identified within those seven original pinpoint areas “are now being cleaned and greened with some form of the PHS LandCare treatments,” according to Hinckley.

During the past year or so, Operation Pinpoint expanded its area of focus from seven to 45 zones across the city.

Within these expanded areas, PHS determined it was already maintaining 5,500 vacant parcels (a mix of both stabilized and non-stabilized) and will continue to do so.

As part of Operation Pinpoint, police captains inform city officials where the city should consider new, additional interventions. This year, the city’s funding that work with $1.3 million for greening and anti-blight initiatives, Hinckley said.

But it is unclear whether the city will invest further to fully stabilize new lots within the pinpoint areas. Discussions are underway about how to continue cleaning and greening efforts and evaluate them going forward, Hinckley said.

Meanwhile, labor conditions seen around the country are playing out in Philadelphia as well – even if they haven’t derailed the city’s cleaning and greening work.

Ongoing obstacles include worker shortages and the rising cost of materials, compounded by chronic problems such as illegal dumping on vacant lots, according to Dalal of PHS.

In terms of future growth, funding remains the biggest challenge for cities like Philadelphia to scale up cleaning and greening efforts.

“Although we are extremely grateful for the funding we do receive and are able to provide an enormous impact due to that funding, we would require more funding to grow the program and to be able to impact entire neighborhoods throughout the city,” Dalal wrote in an email.

The Challenge With Measuring Impact

As for Andrea Vettori’s initial question about whether Sanctuary Farm has affected community safety, that’s harder to discern than you might expect.

We looked at statistics provided by the police department through OpenData Philly on shooting victims going back to 2015 and criminal incidents as far back as 2012, both citywide and in the half-mile area surrounding Sanctuary Farm (the radius used in a 2013 study similar to those Kondo discussed with us).

Initially, records for more than 3,000 of those incidents were unusable because either (1) information was missing or (2) the street addresses and geographic coordinates for the same incident didn’t correspond to the same spot – even after we tried manually correcting errors such as misspellings.

(Similarly, the Philadelphia City Controller’s website notes hundreds of incidents citywide since 2015 simply have not been included on its interactive maps due to location information missing from police records).

We eventually succeeded in making the data usable through manual corrections, running records through a different geocoding program and/or a combination of the two. Since then, the OpenData Philly dataset appears to have been updated so that the overwhelming majority of records’ geographic coordinates are correct.

Our total dataset consisted of hundreds of thousands of incidents; our analyses within a targeted geographic area (around Sanctuary Farm) and shorter timeframes (annually) drew from far fewer records.

We found violent crime rates in the Sanctuary Farm vicinity tended to move in the same direction as Philadelphia overall, though usually rose and fell more dramatically, during the few years before and after Vettori launched the operation. It’s probably too soon to tell how Sanctuary Farm affects neighborhood safety and, even then, more analysis would be needed.

Beyond precise and accurate geographic data, gauging the impact of vacant lot improvement on the surrounding neighborhood would require more than comparing localized statistics to citywide numbers.

Sanctuary Farm’s main growing lot is located at the intersection of North 24th and West Berks streets.

It also would require figuring out whether crime had essentially been “pushed” from one neighborhood into another. That would mean establishing a control neighborhood (as in the Philadelphia-based studies noted above), which was beyond the scope of this story.

Anecdotally, violence in the neighborhood around Sanctuary Farm seems like it’s diminished during the past two decades, according to longtime Sharswood resident Lesheild Myers.

Myers lives across the street from her childhood home, where her mother moved their family in 1971, on the same block as Sanctuary Farm.

“The transitions that I’ve seen this area go through, it’s been good,” Myers said. “We don’t have all that violence like it was. Nowhere near a lot of violence like it was, as they began to do small developments in the area, like the farm.”

As to whether this urban farm has had an impact as well, Myers said it gives “some of the children something else to do besides just roaming the street.”

“It’s not like they have to stand on the corner,” said Myers, who volunteers at Sanctuary Farm. “They come to this corner, and they’re doing stuff in the garden versus standing on the corner and leaning on a wall.”

Priscilla Bennett also cannot definitively say whether Sanctuary Farm has directly affected neighborhood safety. Rather, she thinks it has brought a sense of “calmness of just seeing it” – and that “can change the direction or some of the violence.”

At the same time, Bennett is skeptical about the prospects for converting more vacant parcels into usable green spaces within the neighborhood. Pointing to several new residential buildings going up in the area, she questioned whether developers “see a profit in having a garden.”

“It’s hard to even see any future in greenery,” Bennett said.

New residential construction on previously vacant land along North 22nd Street between West Montgomery and Cecil B. Moore avenues.

As part of efforts to measure the impact that vacant lot remediation can have, researchers also use control neighborhoods to isolate other variables – such as affluence – that can affect crime, rather than compare individual neighborhoods only to citywide metrics, according to University of Michigan researcher Laney Rupp.

Rupp, a project manager, noted the heavy lift undertaken at times by researchers at the University of Michigan Youth Violence Prevention Center. The center studies the impact of community greening interventions in Flint, Youngstown and Camden (researcher Michelle Kondo has contributed her expertise to that project as well).

Rupp said cleaning police data had been a semester-long project for a squad of geographic information systems (GIS) interns – until a data manager came aboard and developed a script that reduced the job to mere hours.

“But that was an investment,” Rupp said.

And it’s an undertaking that often exceeds the capacity of organizations trying to do this work and demonstrate their effectiveness to funders.

In Flint, for example, local officials running the Clean & Green program (a similar, separate initiative from the University of Michigan’s youth violence intervention initiative there) have struggled to demonstrate its effectiveness. That’s curtailed funding, program expansion and pay for city residents doing the work to maintain vacant lots, according to Christina Kelly, director of planning & neighborhood revitalization for the Genesee County (Mich.) Land Bank Authority.

Kelly is convinced the program saves money by “reducing emergency room visits, by improving public health, by reducing violence and the [related] costs.”

Quantitatively documenting the impact, however, is expensive, Kelly said, and essentially prohibitively time-consuming without a dedicated data expert.

“We do an evaluation that we can afford to do, which is asking people,” she said. “And they’ve been saying that it reduces crime. They say that they feel safer. They say that their neighbors feel safer.”

This article is part of The Toll: The Roots and Costs of Gun Violence in Philadelphia, a solutions-focused series from the collaborative reporting project Broke in Philly. You can find other stories in the series here and follow us on Twitter at @BrokeInPhilly.

This article is part of The Toll: The Roots and Costs of Gun Violence in Philadelphia, a solutions-focused series from the collaborative reporting project Broke in Philly. You can find other stories in the series here and follow us on Twitter at @BrokeInPhilly.